T

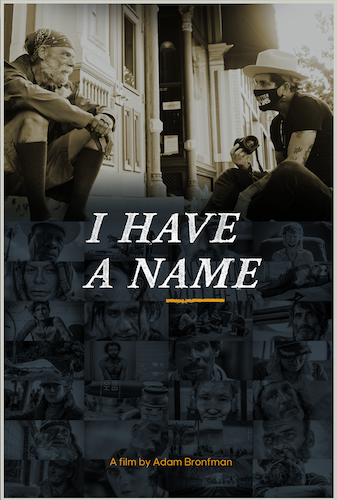

heorem Media honored and proud to present I Have A Name alongside our partner and the Producer of the film, Adam Bronfman. I Have A Name is a Redpoint Digital Production. Please see below for our full press kit for the film, which can be downloaded at the bottom of this page with other promotional assets.

T

heorem Media honored and proud to present I Have A Name alongside our partner and the Producer of the film, Adam Bronfman. I Have A Name is a Redpoint Digital Production. Please see below for our full press kit for the film, which can be downloaded at the bottom of this page with other promotional assets.

LOGLINE

I Have A Name invites audiences to come face to face with the unhoused crisis through the eyes and lens of artist and activist Jon Linton as he takes to the streets to engage with unhoused men and women with compassion and purpose.

SHORT SYNOPSIS

A book of photographs, an art exhibit and now a documentary film, I Have A Name is inspired by the lived experiences of artist and activist Jon Linton, who in 2007 was moved to start making photographic portraits of men and women living on the streets of Phoenix, Arizona. With the addition of a traveling outreach bus, the mission expanded, enabling Jon to engage deeply with unhoused men and women from Phoenix to Portland, creating trust and dignity through the simple approach of asking people’s names. When philanthropist Adam Bronfman became aware of Jon’s work, he felt inspired to produce a film that could capture the unhoused crisis through the eyes of his friend Jon. This urgent and poignant documentary chronicles Jon’s journey to reach out to people in need of not only food, water and essentials, but the compassionate touch of empathy and warmth of human connection.

LONG SYNOPSIS

I Have A Name invites audiences to come face to face with the unhoused crisis through the eyes and lens of artist and activist Jon Linton as he takes to the streets to engage with unhoused men and women with compassion and purpose.

While living in Phoenix, Arizona in 2007, Jon Linton lost a friend to addiction and the streets. To honor his memory, and to bring awareness to the unhoused population living among us in plain sight, Jon picked up a camera with the aim to give an identity and a backstory to the men and women he encountered. When his first subject Chuck was moved to tears when asked his name, Jon knew he had crossed an important bridge to empathy and connection. Some years later, he exhibited his photographs in a gallery show titled “I Have A Name”, the portraits capturing the plight, yet also the beauty and dignity in the faces.

From his Facebook page, Jon cast about for hashtags to usher in a movement and to helm a project he planned to undertake; #LetsBeBetterHumans became the rallying cry behind everything he hoped for humanity. He raised funds selling t-shirts online and through the generosity of the Southwest Institute of Healing Arts who donated a bus, he traveled the country to reach out first-hand to people in need.

In Los Angeles, California, Jon pulls up at tent encampments on Skid Row and meets the human beings forced to live alongside rats, garbage and disease. He is devastated when he encounters a former Marine living there who has taken on the unimaginable task of locating and removing the dead bodies that all too frequently are found amid the squalor. Later, in Venice Beach, Jon meets teenager Aidan, who hasn’t showered in four months and lets him use the shower in his hotel room so he can enjoy the basic human right to clean water. Another man, Michael, longs for the simple joy of music; Jon brings him onto the bus and plays him his favorite song. The men and Jon are brought to tears.

The bus, painted in bright colors and bearing the words Let’s Be Better Humans in giant letters on its side, disarms the men and women living on the streets, allowing Jon to reach possibly dangerous unhoused communities that might otherwise be distrusting of strangers. In Oakland, California, Jon meets DeShaun, a heroin and meth addict who questions the existence of hope. Jon struggles to cope with the emotional price tag of his mission.

As the work takes its toll on Jon, he often feels he has reached the end of his tether emotionally and physically, but in Ashland, Oregon, he engages with Vern, a man who has been on the streets for ten years after an injury left him unable to work. Vern longs to return to his family and his beloved dog, but lacks $50 for a bus ticket. With donations he has raised, Jon is able to help Vern return to the coastal town of Brookings. Two weeks later, Jon receives photos of Vern, looking relaxed, cared for, and happily reunited with his dog; Jon marvels at the transformation before him. This moment, and many others like it, lift Jon up, giving him strength and hope, and although he knows he cannot tackle the enormity of this scourge by his actions alone, he sees firsthand the small measure of humanity he is providing.

Back in 2011, when Jon published a book of his photographs, he was shocked to discover that his proof-reader Christy had lost a son to the streets. Seeing his photographs allowed her to speak openly about her child, rather than hiding behind self-imposed silence and her shame of being thought of as a bad mother. Jon concedes that it is easier to turn away from difficult issues than to face them, but that if his project can create awareness, inspire change and deliver hope to unhoused communities, then maybe we can stop looking past people and really see them for the mothers, fathers, sons and daughters that they are.

LIFE-CENTERED DESIGN INITIATIVE

“We have the opportunity to reimagine, redesign and recreate our future.”

- Bruce Mau

Visionary designers and forward thinkers Bruce Mau and Bisi Williams, co-founders of Massive Change Network, a design agency with a mission to accelerate massive, sustainable change and positive impact for the planet, viewed I Have A Name and were immediately compelled to create initiatives, workshops and curricula around the project. Together with Theorem Media, MCN is working with universities, design institutions and museums to use the documentary as a catalyst to reframe the unhoused crisis as a design challenge.

ABOUT THE PRODUCTION

Genesis

“When your streets become your mental health care providers, it's a poor commentary on the country.”

- Jon Linton

I Have A Name could be described as an “accidental” documentary - an impassioned piece of filmmaking that came about organically through one man’s outreach work and compassion, with no intent other than to honestly reflect the living conditions facing our fellow humans who have met with unforeseen circumstances or who are living in the grip of addiction. But the film’s impact is immeasurable, with those who see it reevaluating their relationship with the unhoused and spawning a growing movement for local action and broader social activism.

Jon Linton remembers his first exposure to the unhoused when he came to New York City in the mid 1980s, fresh out of college. A work colleague warned him about giving handouts to “bums” on the street, but he wasn’t to be dissuaded, responding, “I just got out of college. I know what it's like to be broke and these aren't bums. They're people.” And decades later, this memory has deep resonance, as Linton has spent much of this century engaging with unhoused men and women in Arizona, and across the United States.

After working for Ralph Lauren in New York City for almost five years, Linton started an art magazine in Scottsdale, Arizona, sharing office space with a colleague who had struggled with addiction over several years. Linton describes his ultimate relapse, “His fall wasn't a slow elevator ride to the bottom. It was a free fall. He lost his wife and by virtue of that, he lost a place to live. He lost his battle with addiction, and he ended up dying and homelessness was certainly a part of his story.” In an attempt to process what had happened, Linton decided to act. “I've fooled around with a camera,” he says, “so I thought, I'll talk to a few gallery owners that are close friends. We'll get a gallery show, and we'll see if we can't get photographs of people on the street and this will pay honor to a friend's memory and at the same time give a voice to people that are living in these dire circumstances in the margins.”

Like any big idea, this one took a while to come to fruition and it took Linton several years to pick up his camera. But in November of 2007, with the encouragement of a friend, Linton walked out into the streets to open himself to the reality of what it is to be unhoused. He explains, “Prior to taking the photographs, I volunteered at a shelter for a couple months to understand the plight of those that were living unhoused so that I could get a better understanding about their circumstances and what they were going through.” One of his apprehensions was how to approach the people he encountered. “I was trying to figure out how I was going to have a dialogue, capture a piece of imagery, collect a narrative,” he says, “but at the same time, how I was going to do that with a measure of dignity that didn't look like I was either exploiting the position or creating any shame or guilt.”

The first man Linton approached was a Vietnam veteran holding up a sign asking for help. Linton explained to him that he was a photographer and wanted to honor his late friend and to raise awareness around the unhoused crisis. And then, catching himself, introduced himself and asked the man his name. It was a pivotal moment for both men. “When he started to weep, I knew exactly what he was crying about,” recalls Linton, “so we were both left in a very delicate, emotional state. Both of our eyes were filled with tears. The man replied, ‘My name is Chuck. You have no idea how long it's been since somebody's asked me who I am.’ ”

Reliving that moment still proves to be emotional for Linton and he traces all that followed back to that life-changing interaction. He started collecting photographs, but had no real plans for the project outside of exhibiting them in a gallery show titled “I Have A Name”. At the time he thought it was all he could offer. But organically, due to his commitment as an artist, activist and advocate, Linton found donors, partners and supporters and a new mission evolved under the banner LET’S BE BETTER HUMANS.

The Let’s Be Better Humans Project

“I never thought Let's Be Better Humans was a mandate. It was an invitation, one that we all can embrace.”

- Jon Linton

With the success of the gallery exhibition and an accompanying book of photographs, Linton tapped into social media to spread his message. His Facebook page gathered steam, and Linton created the hashtag #Letsbebetterhumans. Using that hashtag as a motif, Linton designed t-shirts and the profits funded his efforts to continue his outreach efforts. In 2017, K.C. Miller, the founder of the Southwest Institute of Healing Arts reached out to Linton to ask him about using his language around a curriculum they were creating. Instead of selling his slogan, Linton asked simply for help buying an old bus that he had noticed in his neighborhood.

With the help of friends, Linton painted the bus in bright colors with the words LET’S BE BETTER HUMANS in bold letters along the sides. Through money raised on the Facebook page, and donations and some corporate support, Linton and his team were able to provide basic essential items such as water, food, toothpaste, tampons, razors even sleeping bags, tents and clothes. Linton recognizes the dangers he might have faced, but attributes his success rate to his approach of engaging with unhoused men and women with compassion. “There were times that I walked away because I realized that I could be in danger,” he admits. “But I was turned away very few times and I think it was the fact that they knew that I was sincerely interested in trying to create a sense of awareness, because without awareness, there is never any change. Not that I ever professed that we were creating any change, but when somebody's bleeding on the street metaphorically speaking, a band aid is needed.”

The Executive Producer

“In looking through Jon's eyes and listening to Jon's story, I realized that I was able to see things that I wasn't able to see, and I was able to find a level of compassion that I didn't have before.”

- Adam Bronfman

It turned out that Linton’s work was not going unnoticed. An old friend of his, philanthropist Adam Bronfman, had been following the project on Facebook and reached out to Linton, asking to come out on the bus. Linton was surprised to say the least, especially as it was the height of the Covid pandemic and Phoenix temperatures were up around 115 degrees. He continues, “Adam was this man that comes from a very prominent, very wealthy family. You wouldn't expect him necessarily to be on the bus doing the boots on the ground, dirty work.” He further adds, “Adam and his family, his wife, they volunteered many, many times, and then at some point Adam said I think a film should be done here. And I wasn't really keen on that idea. I didn't want to be the subject of a film. I was certainly more comfortable on the other side of the camera.”

Despite Linton’s misgivings, Bronfman felt that the #Letsbebetterhumans story needed to be documented, so he hired videographers Nik Wogen and his son Josh Bronfman to head out on the bus armed with cameras. Bronfman was also a close friend of Karol Martesko-Fenster of Abramorama, with whom he had worked on a five-part docu-series he produced called The Con, exploring the criminal causality of the 2008 financial crisis. Karol was intrigued by what he heard from Adam about the filming, having been personally affected by a close friend who was living on the streets of Los Angeles. Karol urged him to stick with the project, and so they continued the low-budget, “run and gun” style production. Dealing with the weather, the pandemic, and frequent police interference and threats of arrest, Bronfman details why he saw value in Linton’s mission; “He introduced me to this body of work that he was doing, both working directly with homeless people to distribute food and water off his bus, but also to this art,” he says. “And I was so moved by his work.”

Recognizing the enormity of the societal issues surrounding homelessness, Bronfman acknowledges how easy it is to look away, assuming the problem is someone else’s or that other people will find the solutions. “I think that the problem is so large and is so systemic and societal in nature that as individuals we don't know what to do,” he admits. “I still don't have an answer to that, by the way. I don't know exactly what I'm supposed to do. But I do know that the first step was to look at these pictures and to see into the eyes of the people in the portraits and to see them as human beings.”

And Bronfman found himself proud to be working with a man whom he describes as thoughtful, kind and generous. “I think that ultimately Jon's special sauce is that he's willing to be open, honest, vulnerable in the parts of himself that are very hard for most of us to engage with,” he explains, adding, “I think that Jon is an example of someone who is both asking other people to be gentle with him and is willing to be gentle with them and that takes a level of strength that I rarely see.”

During his time out on the road, Linton faced mental and physical exhaustion. But frequently, a new interaction would leave him feeling overcome with gratitude, hope and a deeper understanding of the potential for beauty in connection: a look on someone’s face when given a new pair of shoes; somebody in need passing their food to somebody even hungrier; or a circle of people holding hands and praying for him. These were the things that kept him coming back. But eventually Linton needed to step back from the forward-facing aspect to his mission and he decided to hand the bus off to the organization “Arizona Jews for Justice” which was aligned ideologically with his activism. He states, “It's always been about the marriage of art and advocacy. Adam felt it was important that I stay connected to the project. So I'm involved, but not in the day-to-day routine.” He adds, “The bus has become a social justice instrument, its own entity. It’s not mine.” And Bronfman proudly acknowledges that the bus is busier than ever and goes out almost every day.

Crafting the narrative

“What is the story that we can possibly tell and can we tell the story in 40 minutes?”

- Adam Bronfman

As the film was finishing up principal photography, Karol began talking to Adam about a new non-profit that he was involved with that was coming on the non-fiction storytelling scene with a keen focus on innovation and strategy called Theorem Media. This led to a 90 minute video call between Karol, Adam and Douglas Dicconson, Theorem Media’s Founder and CEO, which sparked the ongoing collaboration. Dicconson was thrilled to be able to participate in the post-production strategy and fine-tuning edit of such important work, acknowledging that it aligned beautifully with Theorem’s mission.

“Theorem Media exists to bring powerful human stories to audiences that have the capacity to change our future,” he says. “This creates massive change simply by fulfilling the basic human desire to experience a good story.” Bronfman concludes, “Ultimately this story is really about Jon and looking through Jon's eyes and listening to Jon's experience. And through that, I was able to understand things about myself, and I wanted to give that experience to other people.”

One of the biggest challenges facing the production team was how to perfect a resonant narrative from the many hours of footage they had. Bronfman took the project to Eric Vaughan and Joe Siebert at Red Point Digital, two collaborators from The Con series project, and invited their fresh perspective. Recalls Bronfman, “I said, here's the story I want to tell. Here's the raw footage. Here's my original conception. Do we have what we need in order to fulfill my original dream?” They responded with a resounding yes and came on board as director and editor respectively. Bronfman adds, “The story in many ways wrote itself. And we really just followed what Jon was telling us. Ultimately, this is a story about a man who is as beautiful a human being as I've ever met. And we just took the visuals to it and we allowed it to come to life.”

Coda

“Everybody on the street has a story and when I sit down and I talk to somebody about their story, I see them differently.”

- Adam Bronfman

Bronfman does not profess to hold the answers to the problems that are reflected on screen but knows that the film has touched all who have seen it, giving them pause to ask “Who am I?”, “How do I engage?”, “What is my role as a human being?” He attributes the film with a powerful, guiding directive; “Ultimately, it's Jon saying, if I can ask someone their name and introduce myself and recognize their humanity and become more human myself, then you can do it too.” Linton concludes, “I think the film is a great legacy for something that I created a long, long while ago. And I hope that at some point we can live in a world where people aren't hungry or are not on our streets because they're mentally ill.”

Massive Change Network

“Bruce and Bisi are trying to take this concept of life-centered design and turn it into a sense of empowerment and agency.”

- Adam Bronfman

In 2023,Theorem Media approached visionary thinker and designer Bruce Mau. Mau and his longtime collaborator Bisi Williams are co-founders of Massive Change Network, a design agency with a mission to accelerate massive, sustainable change and positive impact for organizations and the planet. When the two artists and uber optimists saw I Have A Name, they were instantly eager to be involved. Says Mau, “The film inspired me to think differently about how to frame things that would allow people to move, and to create the kind of impact and action we need to overcome this.” Mau and Williams, who are working with Arizona State University to help reconsider the very nature and structure of education, were so excited by I Have A Name that they proposed a design curriculum around the unhoused crisis. Using the film as a springboard, they currently teach an undergraduate course to design and engineering students, with the goal to redefine the problem, identify the roadblocks to change, create solutions and to work more closely with the unhoused.

As well as teaching the class, Massive Change Network and Theorem Media are collaborating to host screening and design thinking workshops in partnership with major museums and universities in cities such as New York, Washington D.C., Toronto, Chicago and Berlin, with the film serving as the intersection between art and advocacy and the very real work of city planning and social services. Mau elaborates, “Life is a designed life and the beauty of that is, since it is designed, we can redesign it to be more beautiful, more sustainable, more humane. And therefore we have the capacity to change the world.”

Linton was ready for his project to be screened at film festivals, but admits that he was humbled that Bruce Mau wanted to participate and use the film as an educational tool to initiate transformative change. While recognizing the complexity of the issue, he is thankful that the project is now in the creative, unique hands of Mau and excited for the awareness that MCN will bring to the issues. “I'm quietly very optimistic,” he says. “I've heard from Bruce, ‘every time I see it, I cry again.’ He's still touched and I think that it's lovely that he's committed to this and it'll be interesting to see if this as an educational tool can actually create change. I hope it can.” For his part, Bronfman proudly stands behind a project with real-world applications, concluding, “This is a message to people that we do actually have agency and we do have the ability to look at the way our world works and perhaps start working on ways to make it better.”

ABOUT THEOREM MEDIA

Theorem Media is a 501(c)(3) corporation focused on strategy, innovation & research in the independent media ecosystem. Theorem Media exists to bring stories that illuminate the most important topics of our time to audiences that have the capacity to change the future. This approach creates measurable cultural impact by harnessing the basic human desire to experience a good story.

The company was founded in 2019 by CEO & Trustee Douglas Dicconson alongside Innovation & Strategy Officer Karol Martesko-Fenster, who have been collaborating since 2008 on large scale global projects including short film programs GE FOCUS FORWARD – Short Films, Big Ideas, WE THE ECONOMY – 20 Short Films You Can’t Afford to Miss. In 2024 Theorem Media participated in strategic release and marketing campaigns for feature documentary films including Vanessa Hope’s INVISIBLE NATION, FOLLOWING HARRY an intimate portrait of the final twelve years of the Life of Mr. Belafonte and David Smick’s AMERICA’S BURNING executive produced by Michael Douglas & Barry Levinson.

Theorem Media operates as a collaborative coalition of partners including Adam Bronfman, Massive Change Network, Abramorama, Lynne Gugenheim and others.

ABOUT MASSIVE CHANGE NETWORK

Massive Change Network (MCN) is a global design consultancy partnering with visionary leaders to reimagine futures, create meaningful impact and drive transformative — massive — change for organizations and the planet. In a world defined by complex, interconnected challenges, MCN harnesses the power of design to solve critical problems at speed and scale.

Design innovators Aiyemobisi “Bisi” Williams and Bruce Mau co-founded MCN and continue to lead its practice. Applying their proprietary 24 Massive Change Design Principles (MC24®), MCN works with global brands, leading organizations, heads of state, renowned artists and fellow optimists to deliver custom, boundary-pushing solutions.

Working on what they love, Bisi and Bruce’s career-long interests span across seven wicked problems — cities, climate, health, energy, empowerment, demographics and learning.

ADAM BRONFMAN PRESENTS

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THEOREM MEDIA

A RED POINT DIGITAL PRODUCTION

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

ADAM BRONFMAN

FEATURING

JON LINTON

PHOTOGRAPHY

JON LINTON

DIRECTOR

ERIC S. VAUGHN

EDITOR

JOE SEIBERT

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

NIK WOGEN

CAMERA OPERATORS

NIK WOGEN

JOSH BRONFMAN

POST PRODUCTION SUPERVISORS

ERIC S. VAUGHN

JOE SEIBERT

VISUAL EFFECTS

DAVE HAYWARD

JACOB KEETON

LAUREN MOORE

MUSIC SUPERVISOR

ALEX E. TENNENT

COLORIST

ERIC S. VAUGHN

DIALOGUE/SOUND DESIGN/RE-RECORDING MIXER

RICHARD MAURER

ASSISTANT SOUND MIXER

KENNY LLOYD

All Rights Reserved © 2024 Theorem Media Inc.